In modern cosmology, a large-scale web of dark matter and normal matter permeates the Universe. On the scales of individual galaxies and smaller, the structures formed by matter are highly non-linear, with densities that depart from the average density by enormous amounts. On very large scales, however, the density of any region of space is very close to the average density: to about 99.99% accuracy. On scales larger than a few billion light-years, no structures will ever form, owing to the presence and late-time domination of dark energy.

Credit: The Millennium Simulation, V. Springel et al.

Key Takeaways

In modern cosmology, a large-scale web of dark matter and normal matter permeates the Universe. On the scales of individual galaxies and smaller, the structures formed by matter are highly non-linear, with densities that depart from the average density by enormous amounts. On very large scales, however, the density of any region of space is very close to the average density: to about 99.99% accuracy. On scales larger than a few billion light-years, no structures will ever form, owing to the presence and late-time domination of dark energy.

Credit: The Millennium Simulation, V. Springel et al.

Key Takeaways

- We have a concordance picture of our Universe that’s extremely compelling and data driven, and if it’s correct, allows us to calculate the long-term fate of planetary systems, galaxies, and even the entire Universe.

- But this is all based on a vanilla picture of reality: where dark matter doesn’t self-interact, where protons are eternally stable, and where dark energy is a cosmological constant. What if these things aren’t true?

- The answer is that any one of these changes, all of which are allowed by and would be consistent with the full suite of data, would profoundly alter our ultimate, long-term fate. Here’s how.

All throughout the Universe, we can see evidence for not only the “stuff like us” that’s out there, but additional forms of energy that take us beyond the Standard Model of elementary particles and forces. Sure, there’s plenty of normal matter: things like atoms and ions, made up fundamentally of quarks, gluons, and electrons, just like we are. There are stars and planets, but also gas, dust, plasma, and even black holes made from the same raw ingredients that make us up. There are also photons, or quanta of light, and the nearly invisible neutrinos and antineutrinos, all playing detectable, measurable roles in the evolution of our cosmos.

But that doesn’t explain everything we know is out there contributing to our Universe. We know, from observing galaxies, galaxy clusters, and the large-scale cosmic web, that the dominant form of mass in the Universe is not found in the Standard Model, but instead is a mysterious novel substance that we presently call “dark matter.” We know that the Standard Model, with all of its known laws and ingredients, cannot account for the matter-dominated Universe we have, and that some type of new physics must have created the matter-antimatter asymmetry. And we know, from observing the expanding Universe in a variety of ways, that the Universe is actually dominated by a novel form of energy that isn’t a type of matter or radiation at all: dark energy.

We think that we know the general properties of what dark matter is, of what caused baryogenesis, and how dark energy behaves. This creates a picture of our Universe’s far future that’s based in the best science we have today. But if any of those things are different from our simple (and perhaps naive) expectations, then our far future could turn out very, very differently from how we currently expect. Here’s how it breaks down.

The Standard Model of particle physics accounts for three of the four forces (excepting gravity), the full suite of discovered particles, and all of their interactions. Whether there are additional particles and/or interactions that are discoverable with colliders we can build on Earth is a debatable subject, but there are still many puzzles that remain unanswered, such as the observed absence of baryon number violation, with the Standard Model in its current form.

Credit: Contemporary Physics Education Project/CPEP, DOE/NSF/LBNL

The Standard Model of particle physics accounts for three of the four forces (excepting gravity), the full suite of discovered particles, and all of their interactions. Whether there are additional particles and/or interactions that are discoverable with colliders we can build on Earth is a debatable subject, but there are still many puzzles that remain unanswered, such as the observed absence of baryon number violation, with the Standard Model in its current form.

Credit: Contemporary Physics Education Project/CPEP, DOE/NSF/LBNL

If you want to know the fate of anything in the Universe, you have to understand the physics behind how it evolves over time. For the matter in our Universe, the physics that governs it is different depending on whether it’s part of a bound structure or not. If it is part of a bound structure, the spacetime that governs its evolution will be non-expanding, and the separation distance between that particle and any other particle that’s a part of that same system will not be compelled to increase due to the expansion of space in that region. But if that matter particle is not part of a bound structure, then it will recede away from all other bound structures, becoming colder, less dense, and more isolated as time goes on.

In the context of the expanding Universe, the clumps of matter that grow large enough rapidly enough can form these bound structures, and then it’s the space between those clumps that keeps on not only expanding, but whose expansion accelerates due to the presence of dark energy as time goes on. This leads to a web of cosmic structure, where matter clumps along filaments to produce galaxies and groups of galaxies, and then clusters more significantly at the nexus of various filaments, producing clusters and even multiple merging clusters of galaxies. The in-between regions, however, continue expanding, driving the various isolated galaxies, groups, and clusters apart from one another as time marches on.

In between the great clusters and filaments of the Universe are great cosmic voids, some of which can span hundreds of millions of light-years in diameter. The long-held idea that the Universe is held together by structures spanning many hundreds of millions of light-years, these ultra-large superclusters, has now been settled, and these enormous web-like features are destined to be torn apart by the Universe’s expansion, while the cosmic voids continue to grow. Only individually bound galaxies, groups of galaxies, and clusters of galaxies will persist.

Credit: Andrew Z. Colvin and Zeryphex/Astronom5109; Wikimedia Commons

In between the great clusters and filaments of the Universe are great cosmic voids, some of which can span hundreds of millions of light-years in diameter. The long-held idea that the Universe is held together by structures spanning many hundreds of millions of light-years, these ultra-large superclusters, has now been settled, and these enormous web-like features are destined to be torn apart by the Universe’s expansion, while the cosmic voids continue to grow. Only individually bound galaxies, groups of galaxies, and clusters of galaxies will persist.

Credit: Andrew Z. Colvin and Zeryphex/Astronom5109; Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, within any individual bound structure (including our own Local Group of galaxies, with the Milky Way, Andromeda, and the hundreds of smaller galaxies accompanying us), less and less matter flows into them from intergalactic space as the Universe accelerates, placing a cutoff on the total amount of normal matter within it. Over time, the star-formation rate has dropped ever since “cosmic noon” was achieved approximately 10-11 billion years ago; it’s now at just 3% of what it was at its peak, and continues to decline. As time continues to pass, not only will the star-formation rate drop further, but eventually, it will slow to a trickle and then stop altogether.

Star-formation requires neutral clouds of molecular hydrogen, and the more stars that form, the less hydrogen there is. Winds from new episodes of star-formation can expel atoms and ions from galaxies and send them into intergalactic space, and as the gas and dust population within a galaxy goes down, the prospects for forming new stars decline as well. Even though it may taken tens of billions, hundreds of billions, or even many trillions of years, eventually the star-formation rate in whatever our Local Group evolves into will fade away to zero. When the now-existing stars run out of fuel in their cores, they will cease to shine as well.

If the light from a parent star can be obscured, such as with a coronagraph or a starshade, the terrestrial planets within its habitable zone could potentially be directly imaged, allowing searches for numerous potential biosignatures. In the far future, it’s these longest-lived, lowest-mass stars that might be the last locations where life likely persists in the Universe a possibility even hundreds of trillions of years from now.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

If the light from a parent star can be obscured, such as with a coronagraph or a starshade, the terrestrial planets within its habitable zone could potentially be directly imaged, allowing searches for numerous potential biosignatures. In the far future, it’s these longest-lived, lowest-mass stars that might be the last locations where life likely persists in the Universe a possibility even hundreds of trillions of years from now.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

And then, over very long periods of time, everything else will fade away too. The distant, unbound galaxies, groups, and clusters will be accelerated away to beyond the limits of what’s reachable or communicable with an observer in any one bound structure, rendering them inaccessible. The stellar and planetary remnants within any bound structure will gravitationally interact, leading material to either fall into a central, supermassive black hole or to get ejected from the galaxy entirely: a process which should take between 1017 and 1019 years, or millions of times the present age of the Universe.

The persisting clumps of matter should remain stable, with the non-radioactive elements persisting for all eternity. After around 1067 years pass, the lightest black holes will completely decay away, and after around 10110 years, the heaviest ones will have decayed away also. This leads to a scenario for the far future Universe known as a heat death, where everything that remains is in its lowest-energy state (the ground state), and from which no further energy will be able to be extracted or used to do work.

The Universe will be nothing more an isolated smattering of bound clumps of mass — mostly dark matter but with occasional clumps of burned out stars and desolate planetary objects — all separated by vast, inaccessible distances that continue to increase as time goes on. That’s how the Universe ends.

When a black hole either forms with a very low mass, or evaporates sufficiently so that only a small amount of mass remains, quantum effects arising from the curved spacetime near the event horizon will cause the black hole to rapidly decay via Hawking radiation. The lower the mass of the black hole, the more rapid the decay is, until the evaporation completes in one last “burst” of energetic radiation. The longest-lived black holes will be the most massive, with decay timescales exceeding 10^100 years.

Credit: ortega-pictures/Pixabay

When a black hole either forms with a very low mass, or evaporates sufficiently so that only a small amount of mass remains, quantum effects arising from the curved spacetime near the event horizon will cause the black hole to rapidly decay via Hawking radiation. The lower the mass of the black hole, the more rapid the decay is, until the evaporation completes in one last “burst” of energetic radiation. The longest-lived black holes will be the most massive, with decay timescales exceeding 10^100 years.

Credit: ortega-pictures/Pixabay

But what if we’ve assumed something that’s incorrect? After all, this scenario only works under the best current description of reality as we understand it today. It assumes that:

- dark matter is a cold, collisionless, non-interacting (except gravitationally) species of massive particle,

- baryogenesis admitted baryon-violating interactions early on, to create the matter-antimatter asymmetry we observe in our Universe, but that conserves baryon number today and for all the time afterwards, leading to a stable proton,

- and that dark energy is a cosmological constant, and that its energy density and contribution to the expansion rate of the Universe won’t change over time.

All three of these assumptions are consistent with every piece of information we’ve ever collected about the Universe, even if you include the pieces that don’t quite fit, such as the Hubble tension, the evidence for evolving dark energy, the lack of particle physics hints that take us beyond the Standard Model, or the constraints we have on a variety of plausible baryogenesis scenarios.

Nevertheless, there is a tremendous amount of wiggle-room here, and if any one of these three simple (but not necessarily well-established) properties turns out to be wrong, the fate of our whole Universe could be due for a profound cosmic shake-up. Here’s how new physics, on any of these three fronts, would impact our far future.

This supercomputer simulation shows the emergence of a rotating disk after hundreds of millions of years of cosmic evolution from gas and dust; the simulation also includes stars and dark matter, which are not shown here. If the dark matter were visible, it would make an enormous halo much larger, in radius, than the entire size of the image shown here, and would exist irrespective of the stars, gas, and dust inside.

Credit: R. Crain (LJMU) and J. Geach (U. Herts)

This supercomputer simulation shows the emergence of a rotating disk after hundreds of millions of years of cosmic evolution from gas and dust; the simulation also includes stars and dark matter, which are not shown here. If the dark matter were visible, it would make an enormous halo much larger, in radius, than the entire size of the image shown here, and would exist irrespective of the stars, gas, and dust inside.

Credit: R. Crain (LJMU) and J. Geach (U. Herts)

1.) What if dark matter has a self-interaction?

For as long as it’s been proposed, people have been looking for ways to detect dark matter. They have looked indirectly, for astrophysical signals and consequences, finding strong evidence in how matter clumps, clusters, and moves within individually bound structures. They’ve also looked directly, for signs of dark matter particle annihilation (at galactic centers, for example), for interactions with normal matter and with light (both cosmically and within dedicated detectors such as ADMX), and for signatures of dark matter colliding with normal matter particles (through direct detection/recoil experiments).

The indirect signatures are overwhelmingly strong; the direct signatures are consistent with a null effect. This means that it’s eminently plausible, as we currently assume, that dark matter has no interaction with light, normal matter, or itself other than through gravitation alone. If that’s the case, then sure, some dark matter particles will be ejected from the bound galaxies, groups, and clusters that they form giant, diffuse halos around, but most will persist for what’s effectively an eternity. These clumpy halos of matter, even after the last black hole evaporates, should persist.

This animation shows a region of the sky centered on the pulsar Geminga. The first image shows the total number of gamma rays detected by Fermi’s Large Area Telescope at energies from 8 to 1,000 billion electron volts (GeV) — billions of times the energy of visible light — over the past decade. By removing all bright sources, astronomers discovered the pulsar’s faint, extended gamma-ray halo, concluding that this one pulsar could be responsible for up to 20% of the positrons detected by the AMS-02 experiment, disfavoring an annihilating dark matter scenario for this cosmic excess.

Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration

This animation shows a region of the sky centered on the pulsar Geminga. The first image shows the total number of gamma rays detected by Fermi’s Large Area Telescope at energies from 8 to 1,000 billion electron volts (GeV) — billions of times the energy of visible light — over the past decade. By removing all bright sources, astronomers discovered the pulsar’s faint, extended gamma-ray halo, concluding that this one pulsar could be responsible for up to 20% of the positrons detected by the AMS-02 experiment, disfavoring an annihilating dark matter scenario for this cosmic excess.

Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration

But if dark matter does have a self-interaction, the story of our far future could change dramatically. Sure, we might have constraints on direct dark matter signatures, but they could show up at levels that are simply below the threshold of what’s presently observable. One fascinating possibility is that dark matter does interact with itself to form a whole “dark universe” of structure: the dark matter equivalent of baryons, atoms, or some other structure that could serve as the building blocks for larger, more complex structure.

The key is recognizing that all our constraints imply is that there’s an upper limit to the rate, or timescale, on which these processes can occur. Our longest-running experiments have lasted for decades, or around 109 seconds. Planet Earth and the Sun have been around 4.5 billion years, or around 1017 seconds. But what if dark matter makes structures on long timescales: scales far longer than the age of the Universe, like sextillions or even googols of years?

It would mean that the “heat death” scenario will be all wrong, because there will be a new way of extracting energy and performing work in the Universe. Even if its small, the discovery of any way that dark matter isn’t purely collisionless or non-interacting through a force other than gravity would profoundly change our ultimate cosmic fate.

The proton isn’t just made of three valence quarks, but rather contains a substructure that is an intricate and dynamic system of quarks (and antiquarks) and gluons inside. The nuclear force acts like a spring, with negligible force when unstretched but large, attractive forces when stretched to large distances. To the best of our understanding, the proton is a truly stable particle, and has never been observed to decay, despite the allowable pathways that permit its decay (at right) within SU(5) and other grand unification scenarios.

Credit: Argonne National Laboratory (L); J. Lopez, Reports on Progress in Physics, 1996 (R)

The proton isn’t just made of three valence quarks, but rather contains a substructure that is an intricate and dynamic system of quarks (and antiquarks) and gluons inside. The nuclear force acts like a spring, with negligible force when unstretched but large, attractive forces when stretched to large distances. To the best of our understanding, the proton is a truly stable particle, and has never been observed to decay, despite the allowable pathways that permit its decay (at right) within SU(5) and other grand unification scenarios.

Credit: Argonne National Laboratory (L); J. Lopez, Reports on Progress in Physics, 1996 (R)

2.) What if baryon violating interactions still occur, and the proton is inherently unstable?

Just as we have constraints that dark matter doesn’t interact, we also have strong constraints on the stability of the proton. Through giant, long-term experiments that are sensitive to proton decay (often with the same experiments that are sensitive to neutrino detection or possible dark matter detection), we’ve constrained the lifetime of the proton to be greater than around 1034 years, or a septillion times longer than the present age of the Universe. This has been enough to rule out many scenarios for baryogenesis: the ones that would lead to an unstable proton with a lifetime of less than the constrained value, including the standard SU(5) Georgi-Glashow unification scenario, both with and without supersymmetry.

But again, this is just an upper limit. It’s possible that the proton is unstable, that there are actually no truly stable atomic nuclei on the periodic table, and that all of the atom-and-ion-based normal matter we know of will someday decay.

And decays are great for the Universe’s potential, because all decays liberate energy and leave you in a lower-energy state. Liberated energy is energy that can be used to do work, to power processes, or to extend the lifetime of — and what’s possible within — the Universe. The surviving bound structures, even long-term, could someday again house physically interesting, perhaps even metabolic, processes.

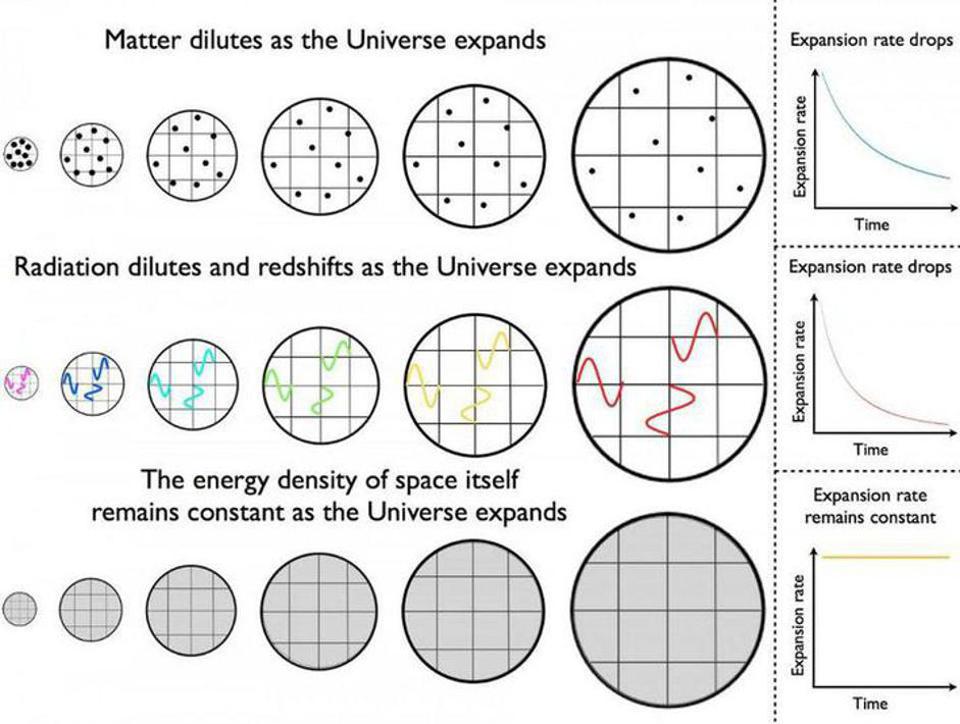

While matter and radiation become less dense as the Universe expands owing to its increasing volume, dark energy is a form of energy inherent to space itself. As new space gets created in the expanding Universe, the dark energy density remains constant.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

While matter and radiation become less dense as the Universe expands owing to its increasing volume, dark energy is a form of energy inherent to space itself. As new space gets created in the expanding Universe, the dark energy density remains constant.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

3.) What if dark energy turns out not to be a cosmological constant, but rather is evolving?

This one is particularly exciting if you want to change the fate of the Universe, because it doesn’t just change the “heat death” part by pushing it out or giving us a new source of energy to draw upon for increasing the entropy of the Universe further than our presently known physics allows us to go. Instead, if we allowed dark energy to evolve — rather than insisting that it remain as a cosmological constant — then it wouldn’t just be the individual clumps whose fates would be different from the standard picture, but the Universe as a whole. After all, dark energy represents the majority of the Universe’s energy, and changing how that energy behaves could change the entire behavior of the Universe.

The reason that the Universe is going to end as a cold series of disconnected, isolated clumps of matter is because of dark energy. As the matter density drops (because the volume of the Universe increases), dark energy — which behaves as a form of energy inherent to space itself in the cosmological constant case — becomes relatively more and more important. Because dark energy has both an energy density and a strong, negative pressure, it ensures that the Universe will always expand, and that distant “bound clumps” will speed away, faster and faster, from one another as time goes on. And therefore, that’s how the Universe will end.

Looking at the data points from DESI (top row) or from the various supernova collaborations (bottom row), it’s very clear that the data, at this point in time, is not sufficiently good to robustly discriminate between the various options for how dark energy is behaving in the Universe. The fact that the three different supernova samples, DESY, Union, and Pantheon+, give such different answers from one another should be a troubling indication that we haven’t yet uncovered the full story.

Credit: DESI Collaboration/M. Abdul-Karim et al., DESI DR2 Results, 2025

Looking at the data points from DESI (top row) or from the various supernova collaborations (bottom row), it’s very clear that the data, at this point in time, is not sufficiently good to robustly discriminate between the various options for how dark energy is behaving in the Universe. The fact that the three different supernova samples, DESY, Union, and Pantheon+, give such different answers from one another should be a troubling indication that we haven’t yet uncovered the full story.

Credit: DESI Collaboration/M. Abdul-Karim et al., DESI DR2 Results, 2025

But if dark energy isn’t a constant, all bets are off. There is circumstantial (but not conclusive) evidence that dark energy may evolve over time, and if so, then many new possible fates suddenly arise.

- Dark energy could strengthen, and if it’s pressure becomes more negative than a cosmological constant’s, then the cosmic acceleration will intensify, and either a Big Rip (where space tears itself apart) or a rejuvenated scenario (where the increased energy density triggers a new hot, dense, Big Bang-like state) could ensue.

- Dark energy could weaken and disappear entirely, causing the cosmic expansion to asymptote towards zero, rendering the distant groups reachable and communicable to one another.

- Or dark energy could weaken and then flip signs, leading to a cosmic recollapse and a Big Crunch, with a potentially cyclic scenario (and a new Big Bang-like state) emerging in the future.

These are three of the big puzzles facing modern cosmology: what the nature, behavior, and properties of dark matter are, how the matter-antimatter asymmetry arose and whether atomic nuclei are truly stable, and what the nature and future evolution of dark energy are. In the simplest, most “vanilla” scenarios, dark matter is non-interacting, baryogenesis occurred only once early on and leaves eternally stable atomic nuclei behind, and dark energy is a pure cosmological constant, leading to our current “consensus” fate. But if the solution to any (or all) of these puzzles turn out to be different from our present ideas, our ultimate cosmic fate is suddenly up for grabs. In many ways, that’s the most exciting exploratory frontier of all!

Tags particle physicsSpace & Astrophysics In this article particle physicsSpace & Astrophysics Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all. Subscribe