- News

- World

- Europe

The law does not apply to people with mental illnesses

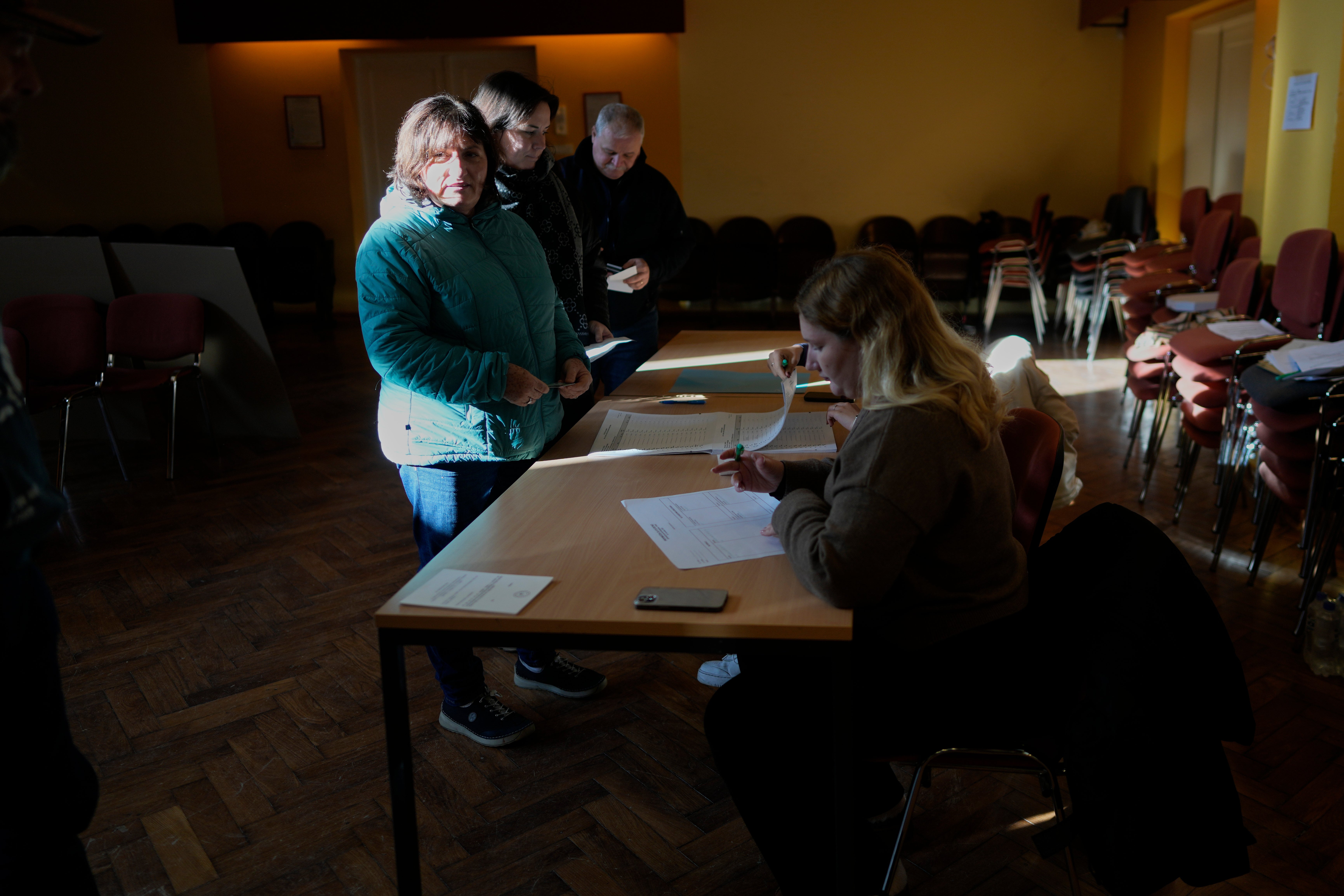

Ap CorrespondentSunday 23 November 2025 11:55 GMT open image in galleryVoters register at a polling station during the referendum on assisted dying for terminally ill patients, in Domzale, Slovenia, Sunday, Nov. 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Darko Bandic) (Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved)

open image in galleryVoters register at a polling station during the referendum on assisted dying for terminally ill patients, in Domzale, Slovenia, Sunday, Nov. 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Darko Bandic) (Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved)

On The Ground newsletter: Get a weekly dispatch from our international correspondents

Get a weekly dispatch from our international correspondents

Get a weekly international news dispatch

Email*SIGN UP

Email*SIGN UPI would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our Privacy notice

Slovenia has once again put the contentious issue of assisted dying to a public vote, with citizens heading to the polls on Sunday for a referendum on a law that would permit terminally ill patients to end their lives.

This follows the small European Union nation’s parliament passing the legislation in July, after a non-binding public consultation last year showed support.

However, opponents successfully gathered over 40,000 signatures, compelling another national vote on the divisive matter. The proposed law grants mentally competent individuals, who face no prospect of recovery or endure unbearable pain, the right to assisted dying. Under its provisions, patients would self-administer lethal medication, subject to approval from two doctors and a mandatory consultation period.

The law does not apply to people with mental illnesses.

Backers include the liberal government of Prime Minister Robert Golob. They have argued that the law gives people a chance to die with dignity and decide themselves how and when to end their suffering.

open image in galleryA voter casts her ballot at a polling station during the referendum on assisted dying for terminally ill patients, in Domzale, Slovenia, Sunday, Nov. 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Darko Bandic) (Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved)

open image in galleryA voter casts her ballot at a polling station during the referendum on assisted dying for terminally ill patients, in Domzale, Slovenia, Sunday, Nov. 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Darko Bandic) (Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved)Opponents include conservative groups, some doctors associations and the Catholic church. They say that the law goes against Slovenia's constitution and that the state should work to provide better palliative care instead.

The law will be rejected if a majority of people who cast ballots vote against, and they represent at least 20% of the 1.7 million eligible voters. Recent opinion polls in Slovenia have shown more people are in favor of the law than oppose it.

If the law remains in place, Slovenia will join several other EU countries that have already passed similar laws, including neighboring Austria and the Netherlands.