- Home

Edition

Africa Australia Brasil Canada Canada (français) España Europe France Global Indonesia New Zealand United Kingdom United States Edition:

Global

Edition:

Global

- Africa

- Australia

- Brasil

- Canada

- Canada (français)

- España

- Europe

- France

- Indonesia

- New Zealand

- United Kingdom

- United States

Academic rigour, journalistic flair

Academic rigour, journalistic flair

Getty Images

‘Forever chemicals’ contaminate more dolphins and whales than we thought – new research

Published: November 24, 2025 1.47am GMT

Karen A Stockin, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University, Emma Betty, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University, Frédérik Saltré, University of Technology Sydney, Australian Museum, Katharina J. Peters, University of Wollongong

Getty Images

‘Forever chemicals’ contaminate more dolphins and whales than we thought – new research

Published: November 24, 2025 1.47am GMT

Karen A Stockin, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University, Emma Betty, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University, Frédérik Saltré, University of Technology Sydney, Australian Museum, Katharina J. Peters, University of Wollongong

Authors

-

Karen A Stockin

Karen A Stockin

Professor of Marine Ecology, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University

-

Emma Betty

Emma Betty

Research Officer in Cetacean Ecology, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University

-

Frédérik Saltré

Frédérik Saltré

Senior lecturer in Ecology and Biogeography, University of Technology Sydney; Australian Museum

-

Katharina J. Peters

Katharina J. Peters

Lecturer in Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong

Disclosure statement

Frédérik Saltré receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Emma Betty, Karen A Stockin, and Katharina J. Peters do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

University of Technology Sydney provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

University of Wollongong, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University, and Australian Museum provide funding as members of The Conversation AU.

Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa – Massey University provides funding as a member of The Conversation NZ.

View all partners

DOI

https://doi.org/10.64628/AA.eqw9fu5hx

https://theconversation.com/forever-chemicals-contaminate-more-dolphins-and-whales-than-we-thought-new-research-269928 https://theconversation.com/forever-chemicals-contaminate-more-dolphins-and-whales-than-we-thought-new-research-269928 Link copied Share articleShare article

Copy link Email Bluesky Facebook WhatsApp Messenger LinkedIn X (Twitter)Print article

Nowhere in the ocean is now left untouched by a type of “forever chemicals” called “per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances”, known simply as PFAS.

Our new research shows PFAS contaminate a far wider range of whales and dolphins than previously thought, including deep-diving species that live well beyond areas of human activity.

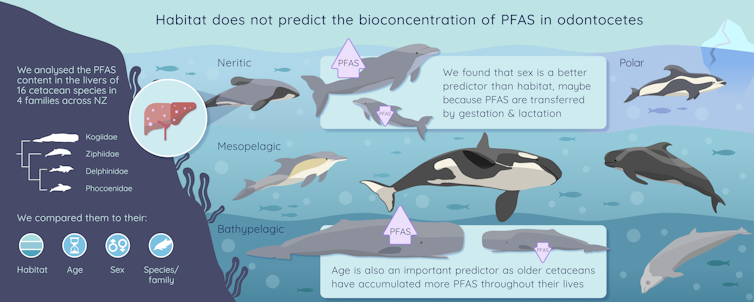

But most surprising of all, where an animal lives does not predict its exposure. Instead, sex and age are stronger predictors of how much of these pollutants a whale or dolphin accumulates in its body.

This means chemical pollution is more persistent and entrenched in ocean food webs than we realised, affecting everything from endangered coastal Māui dolphins to deep-diving beaked and sperm whales.

This graphic shows that PFAS contamination affects a range of marine mammals, from nearshore dolphins to deep-diving predators.

Science of the Total Environment, CC BY-ND

This graphic shows that PFAS contamination affects a range of marine mammals, from nearshore dolphins to deep-diving predators.

Science of the Total Environment, CC BY-ND

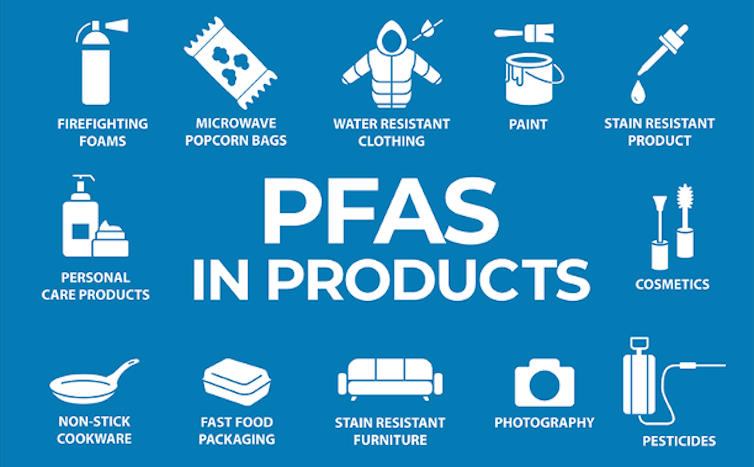

PFAS were originally designed to make everyday products more convenient, but they have ultimately become a widespread environmental and public health concern.

Our work provides stark evidence that no part of the ocean is now beyond the reach of human pollution.

What are PFAS, and why are they a problem?

PFAS are a group of more than 14,000 synthetic chemicals that have been used since the 1950s in a wide range of everyday products. This includes non-stick cookware, food packaging, cleaning products, waterproof clothing, firefighting foams and even cosmetics.

Many everyday products contain PFAS.

Author provided, CC BY-SA

Many everyday products contain PFAS.

Author provided, CC BY-SA

They’re known as forever chemicals because they don’t break down naturally.

Instead, they travel through air and water, eventually reaching their final destination: the ocean. There, PFAS percolate through seawater and sediments and enter the food web, taken up by animals through their diet.

Once inside an animal, PFAS can attach to proteins and accumulate in the blood and organs such as the liver, where they can disrupt hormones, immune function and reproduction.

Like humans, whales and dolphins sit high in the food web, which makes them especially vulnerable to building up these pollutants over their lifetime.

Whales and dolphins are the ocean’s canaries

Marine mammals are an early warning system of the ocean. Because they are large predators with long lifespans, their health reflects what’s happening in the wider ecosystem, including risks that can affect people, too.

This idea is at the heart of the OneHealth concept, which links environmental, animal and human health.

New Zealand is one of the best places in the world to study human impacts in a OneHealth framework. More than half of the world’s toothed whales and dolphins (odontocetes) occur here, making Aotearoa a rare hotspot for marine mammals and an ideal place to assess how deeply PFAS have entered ocean food webs.

We analysed liver samples from 127 stranded whales and dolphins, covering 16 species across four families, from coastal bottlenose dolphins to deep-diving beaked whales.

For eight of these species, including Hector’s dolphins and three beaked whale species, this was the first time PFAS had ever been measured globally.

PFAS contamination is an additional stress factor for Hector’s dolphins, which are endemic to New Zealand and already threatened.

Getty Images

PFAS contamination is an additional stress factor for Hector’s dolphins, which are endemic to New Zealand and already threatened.

Getty Images

We expected coastal species living closer to pollution sources to show the highest contamination, with deep-ocean species being much less exposed.

However, our results told a different story. Habitat played only a minor role in predicting PFAS levels. Some deep-diving species had PFAS concentrations comparable to (or even higher than) coastal animals.

It turns out biology matters more than habitat. Older, larger animals had higher PFAS levels, indicating they accumulate these chemicals over time.

Males also tended to have higher burdens than females, consistent with mothers transferring PFAS to their calves during pregnancy and lactation. These patterns were consistent across all major types of PFAS chemicals.

Why this matters

Our findings show PFAS contamination has now entered every layer of the marine food web, affecting everything from nearshore dolphins to deep-diving predators.

While diet is a major exposure pathway, animals could also be absorbing PFAS through other mechanisms, including potentially their skin. PFAS may further interact with other stressors, including climate change, shifting prey availability and disease, adding further pressure to species already under threat.

Knowing that PFAS are present across different habitats and species raises urgent questions about their health impacts. Are these chemicals already affecting populations? Could PFAS contamination weaken immunity and increase disease risk in vulnerable species, such as Māui dolphins?

Understanding how PFAS exposure affects reproduction, immunity and resilience to environmental pressures is now central to predicting whether species already under threat can withstand accelerating environmental change.

Even the most remote whales carry high PFAS loads and we know humans are not isolated from these contaminations either. Answering these questions is not optional but essential if we want to protect both marine wildlife and the oceans we all depend on.

The research was a trans-Tasman collaboration which also included Gabriel Machovsky at Massey University, Louis Tremblay at the Bioeconomy Science Institute and Shan Yi at the University of Auckland.

- New Zealand

- Whales

- Dolphins

- Marine pollution

- OneHealth

- PFAS

Events

Jobs

-

Associate Lecturer, Social Work

Associate Lecturer, Social Work

-

Lecturer in Paramedicine

Lecturer in Paramedicine

-

Lecturer, Communication Design

Lecturer, Communication Design

-

Leading Research Centre Coordinator

Leading Research Centre Coordinator

-

Chairperson, Animal Ethics

Chairperson, Animal Ethics

- Editorial Policies

- Community standards

- Republishing guidelines

- Analytics

- Our feeds

- Get newsletter

- Who we are

- Our charter

- Our team

- Partners and funders

- Resource for media

- Contact us

-

-

-

-

Copyright © 2010–2025, The Conversation

Associate Lecturer, Social Work

Associate Lecturer, Social Work

Lecturer in Paramedicine

Lecturer in Paramedicine

Lecturer, Communication Design

Lecturer, Communication Design

Leading Research Centre Coordinator

Leading Research Centre Coordinator

Chairperson, Animal Ethics

Chairperson, Animal Ethics